Here is the conundrum of Maine’s floating camps bill

By Julie Harris, Bangor Daily News Staff

Floating camps are a growing problem, according to those who steward the state’s waters for the people of Maine.

They block the water view of taxpaying residents, threaten the water they are on with pollution and avoid the state’s laws by being nonconformist, easily falling between various agencies’ jurisdictions, thus avoiding regulation and penalties.

They look and feel like the camps people build on land that contribute to tax coffers and comply with shore setbacks, Department of Environmental Protection regulations and town codes. But they are on floats, can be anywhere in the water and have zero regulation.

Some towns have tried to deal with them through local ordinances, but there is nothing in state law that addresses whose jurisdiction they fall under and what distinguishes them from a house boat.

Bring in LD 1763, An Act to Regulate Nonwater-dependent Floating Structures on Maine’s Waters, sponsored by Rep. Allison Hepler, D-Woolwich, which is under the scrutiny of the Legislature’s Joint Standing Committee on Inland Fisheries and Wildlife right now.

The bill defines floating camps as “nonwater-dependent structures,” and includes specific definitions for house boats, motor boats, docks and other entities found on or around Maine’s waters.

The bill is direct and strict and outlines daily fines and a 24-hour timeframe for removing such buildings from the water or the state can take possession and do what they want with them.

There are exceptions for water toys, ice fishing shacks and a handful of similar structures, but there is no specific allowance for businesses contained in or that use floating buildings.

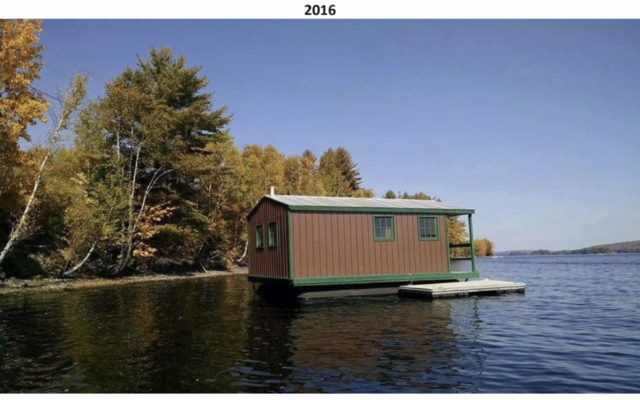

One such business is DeMillo’s on the Water, a floating restaurant that is moored at a Portland marina and is well-known across the state, and another is a tourist business that offers a floating camp tied to a private dock as one of the places available to stay on a privately owned island on Annabessacook Lake in Monmouth.

Both of them have been in business for several years. Neither appears to be violating any other regulations and they seem to be environmentally conscious.

And neither of them would be allowed under the potential law currently being considered.

The IF&W committee doesn’t want to force them and other enterprises like them out of business, according to committee member comments during the public hearing a couple weeks ago, but they also don’t want to simply allow floating buildings that already exist but are not house boats to remain indefinitely where they are without standards, restrictions and regulation.

Establishing a sweeping grandfather clause would make all current floating nonwater-dependent structures legal, including DeMillo’s, Nautilus water house on Annabessacook Lake and Robinhood Marine Center in Georgetown.

But it wouldn’t solve the problem of floating camps moored in front of land-bound camps onshore.

And it would create a new set of problems, such as how to prove a floating camp was in place before the legislation, how to make sure the buildings don’t deteriorate to the point that they become a hazard and how to address potential environmental concerns.

And what on earth do you say to the person who is looking out of their land-based camp window and has a big floating camp smack in the middle of their view?

The Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, the Maine Department of Marine Resources, the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, the Maine Department of Environmental Protection and several others have been grappling with this issue since 2021.

This bill is the result of that, but it could be dead in the water if a compromise cannot be reached soon on the grandfathering issue. The Legislature is running out of time this session.

A work session on the bill was continued from May 12 to May 14, to discuss adding a grandfather clause that would protect businesses but still address the real problem of unregulated floating camps. The committee could vote on it if revisions are made to its members’ satisfaction.

It’s a dilemma that could stall the legislation and force it into the next session, allowing even more of these to pop up on Maine’s water landscape.