Our public lands shouldn’t be sold to the highest bidders to fund tax cuts

By Jeremy Sheaffer, The Wilderness Society Maine director

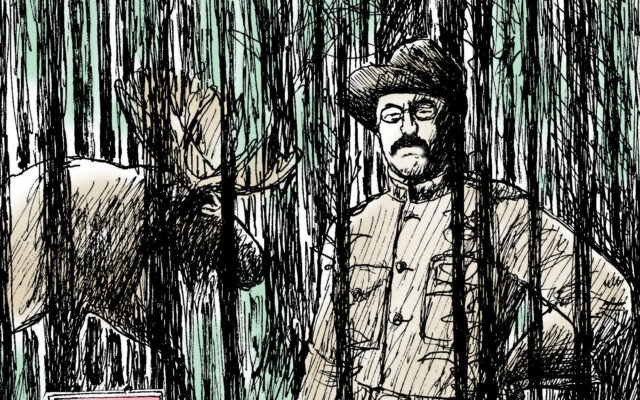

Theodore Roosevelt first came to the North Woods in 1878 in search of himself. He was still a young man then, craving backcountry hardship far from the stuffy confines of Harvard. It worked: Roosevelt’s experiences over a year of periodic visits — hunting, canoeing, happily shivering in the snow, often in and around what is now Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument — helped prove his mettle, and he later wrote that he owed “a personal debt to Maine” for those wilderness rigors.

How many of us have been similarly transformed by our public lands and wild places? Whether taking our kids on vacation or just enjoying the opportunity to hunt and fish beyond our property lines, these are the moments that define and fulfill us, in treasured places like Acadia National Park, Katahdin and the Appalachian Trail, plus nearly 60 national historic and natural landmarks like the Blaine House and Harriet Beecher Stowe House.

And though Mainers have a special relationship with public lands, these places belong to Americans everywhere. They are our national outdoor heritage and an irreplaceable source of beauty and inspiration that attracts visitors both locally and from around the world.

All this makes the events of the last few months especially troubling.The chaos and dysfunction brought to bear by the Trump administration and their enablers in Congress is now threatening America’s public lands, too. Congressional leaders aligned with the White House are considering selling public lands to the highest bidder to fund priorities like tax cuts for the wealthy. If public lands are sold off, the rich and powerful could sell the rights to mine and drill in places where we once hiked and camped. If these places are sold off and spoiled by development, they’re gone for good.

The vast majority of Americans oppose the sale of public lands. Nevertheless, this threat is picking up steam. Earlier this year, the House of Representatives changed rules to make it easier to sell public land, and last month, the Senate rejected a plan to protect public lands from being sold off. May 9 is the deadline for congressional committees to submit their final budget proposals. Unless the outcry is loud, public land sales could slip in with little warning.

Mainers have a special responsibility to take notice of these developments — not just because we love public lands, but because our two senators’ votes will play a major role in determining their fate. It can be argued, as Maine goes, so goes our public lands. U.S. Sen. Angus King voted for the amendment that would have protected our public lands from liquidation, but U.S. Sen. Susan Collins did not. It’s time for her to take a stand.

Roosevelt never returned to the North Woods after September 1879, but he revered wild places all his life. In 1903, while speaking at a ceremony at Yellowstone National Park, Roosevelt devoted loving attention to the park’s plants and animals, but he said its key feature was its “essential democracy,” the fact that it is held “for the people as a whole,” not sectioned into private game reserves for the wealthy. Roosevelt had lived a full life in the years since leaving Katahdin. In that time, his view of the wild had expanded. Once, he’d seen it as a sort of personal proving ground; now, with age, he saw that it was much more besides — a great resource for all Americans, and one that must never be privatized or diminished.

Our strong sense of place, including our public lands, is part of what makes us Mainers. With our fundamental values on the line, it’s time for our leaders in Washington to stand up for the “essential democracy” of our public lands — not for the Trump administration and their billionaire buddies.