Piscataquis residents fear region could ‘become Bar Harbor’ with new Moosehead ski resort

Neighbors of a proposed $113.5 million year-round ski resort in Piscataquis County want their concerns about the project addressed before the development goes any further.

To that end, the Maine Land Use Planning Commission could decide next week whether there will be a public hearing on the Moosehead region proposal, further delaying a project started more than three years ago. Supporters of the project see a sizable boost for the economically depressed county by increasing year-round employment and attracting more people to the area who may start businesses of their own.

The ski resort developer, Perry Williams of Big Lake Development LLC, filed an application in March 2021 for a permit to develop phase one, which calls for a new six-seat chairlift, base ski lodge, 60-room boutique hotel, a brew pub/taphouse and more. The next phase would include a 150-200 slip marina and nearly 500 residential units.

SKI RESORT – The backside of the base ski lodge in Big Moose Township on Jan. 24.

Area residents want to see the Moosehead Lake region and Greenville succeed economically, but too much growth could mean the area would “lose its specialness,” said Chris King, secretary of the residents group Moosehead Region Futures Committee. Logistically, it’s a difficult place to live, but natives remain and others move to the area for the small community, access to nature and more.

“There’s a constant tension,” he said. “None of us want to see this place become Bar Harbor.”

The planning commission will vote during a virtual meeting scheduled for Wednesday on whether to hold a public hearing to hear concerns brought up by the Moosehead Region Futures Committee and a Greenville area resident about financing, sewage disposal and some of the features to be built.

The proposed ski resort, referred to as Big Moose Resort in the application, would replace the Moose Mountain ski resort whose owner, James Confalone of Florida, the state sued in 2016 for failing to maintain the property. Williams has a purchase and sales agreement with Confalone.

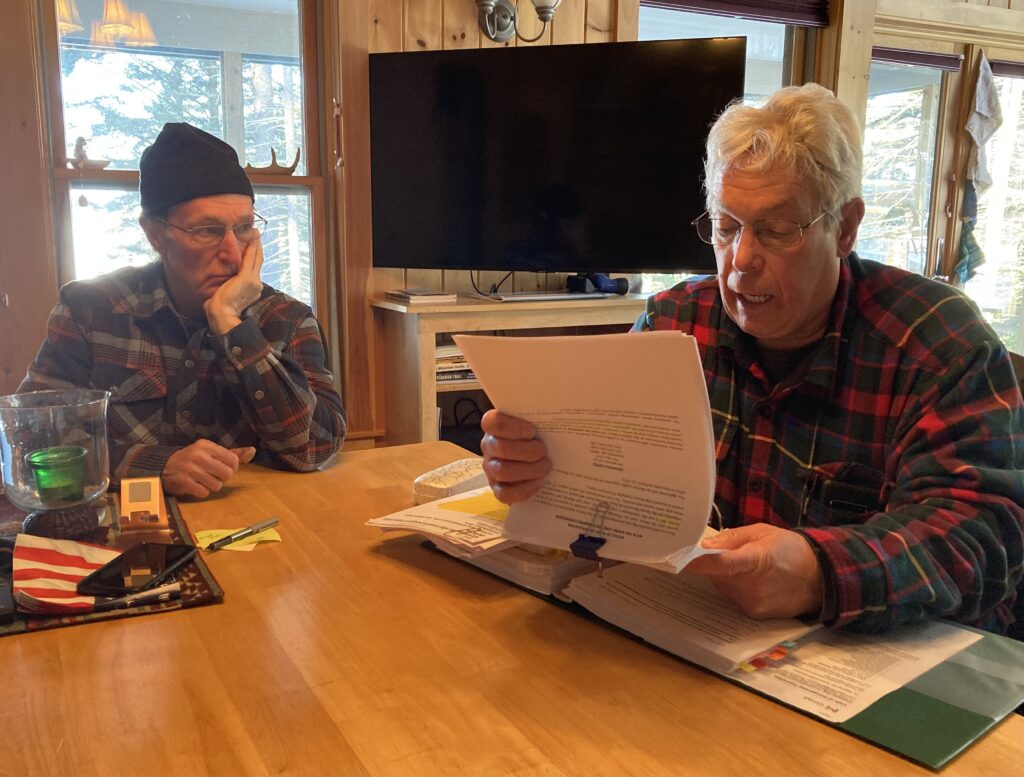

HEARING REQUESTED – From left, Moosehead Region Futures Committee member Bill Baker listens as Chris King, the group’s secretary, reads about the Maine Land Use Planning Commission’s public hearing process at Baker’s home in Greenville Junction on Jan. 24. The nonprofit residents group requested a public hearing on the proposed year-round ski resort on Big Moose Mountain.

“Review of protected natural resources and potential undue adverse effects to existing uses, scenic character and natural resources is currently ongoing,” according to a memorandum posted this week by the planning commission.

Commission staff requested additional information regarding the proposed sewer line from the ski resort to the Moosehead Sanitary District, said Stacie Beyer, the agency’s acting executive director. Information is needed about “the projected amount of wastewater from the project and the ability of the sanitary district to accept the additional volume in terms of the district’s wastewater discharge license.”

The Moosehead Region Futures Committee, a nonprofit residents group that acts as a watchdog to limit harm of commercial and industrial development in the Moosehead Lake area, wrote in its request for a public hearing that it is not opposed to redeveloping the ski area.

A process that allows people to question the proposed redevelopment as thoroughly and openly as regulations allow would serve the public’s interest, the request said.

SNOW-COVERED – A bench sits buried in the snow outside the abandoned hotel at the ski resort on Big Moose Mountain on Jan. 24. The hotel and other areas of the ski resort have fallen into decrepitude over the years. A developer has proposed a plan to redevelop the space into a year-round resort with features such as a new six-seat chairlift, base ski lodge, 60-room boutique hotel and more.

The developer’s financial capacity to complete the project and sewage disposal, particularly if the proposed residential units in phase two are built and occupied, are areas of concern, said Chris King, the committee’s secretary.

He also questioned why the redevelopment is broken into two phases rather than considered one project. Without construction of the 483 proposed residential units in phase two, there will be no property tax revenues to pay the debt service on the bonds that are supposed to finance phase one, the committee’s request said.

“The community is concerned that there isn’t yet another effort made on the mountain that in a few years fizzles out because it’s not financially viable,” King said.

Karyn Ellwood, who is from the Poughkeepsie, New York, area and now lives in the unorganized territory of Misery Gore just south of Rockwood, pointed to similar questions when she submitted the other request for a public hearing.

“I moved here because I liked what was here, and I wanted it to remain this way,” she said. “I’m a huge hiker and I love the outdoors. I am not against the ski area, but I am against uncontrolled development.”

Ellwood also wondered about uphill capacity and operating expenses, specifically whether zoning for the permit allows windmills or solar panels to be installed on Big Moose Mountain to defray operating costs.

“If we’re putting in close to 500 condominiums and a 60-room hotel, and we’re attracting all these people, do we have the uphill capacity to not have two-hour lines on the lifts?,” she said.

Bill Baker, who had owned a campground in Stonington before moving to Greenville Junction more than two years ago to enjoy retirement in a quiet community, worries about the influx of residents and visitors. The ski resort redevelopment has the potential to create a crowded downtown and heavy traffic along Pritham Avenue, in turn putting stress on residents and local facilities, he said.

If developers rework their plans for a marina, it would require gasoline and diesel fuel on the shore of the lake. Motor boats could spill gas and oil, Baker said.

“The marina is right next to an estuary. …There’s turtles, eagles, great blue herons, all kinds of wildlife in that estuary,” he said. “That marina is right there, in the mouth of it. That’s very concerning to me.”

Baker would like to see a commitment from developers to put a number of acres into conservation so the land could be open to the public for recreation.

Matt Dieterich, executive vice president of James W. Sewall Co. which is responsible for the permitting, declined to comment about specific concerns, explaining that those involved with the project are conforming with the planning commission’s guidelines and rules, providing additional documents when needed and are letting the process play out.

“We remain excited about the project,” he said. “We’re beyond interested in the ability to bring economic development to the area. That’s always been one of the prime tenets of the project — making it something the community can be proud of and providing not just seasonal jobs, but year-round jobs for people.”

The local community has been receptive to the proposed project and there has been a lot of general support, Dieterich said.

“We’ve had good dialogue with the LUPC to try to make this a well-recieved project from an environmental standpoint — a resort that fits in with the community,” he said.