In the woods of Baxter State Park, this unexpected woodland friend shared crackers

By Tim Caverly

Sitting on a rock in the Maine wilderness, a boy offers a saltine cracker to a tame deer. Then suddenly the whitetail does a sideways-somersault and vanishes. Could a black bear or Lynx be at hand?

As a youth, I often stayed with my brother Buzz during his 46 years in Baxter State Park. He began his career as a ranger at Abol Campground, eventually moving through the ranks to Park Director, from which he retired in 2005. During those years, the game sanctuary of Katahdin was my classroom for outdoor education. Every spring I reflect on those early days.

It was June, school vacation had begun and at 13, I was accompanying my brother to Baxter’s Russell Pond Campground in T4R9 WELS. While a popular area for hiking, the encampment was a long walk in.

After purchasing groceries, we drove 26 miles from Millinocket to the Park’s Roaring Brook Campground. Parking the car, we donned backpacks for a 7-mile hike. Buzz’s load was a hefty 50 pounds, my Kelty Trekker Backpacker held a lighter 25 pounds. We carried enough supplies to last 10 days. Our provisions included two cartons of Saltine crackers.

Slapping blackflies along the three-hour trek, we finally arrived at the Russell Pond Ranger’s camp. After storing groceries in mouse-proof containers, it was time for supper. While we were cooking spaghetti under the glowing hiss of propane lights, from outside came the sound of Grandma the Deer stomping her feet. We don’t really know her age, but the whitetail visited so often, she was considered an old friend.

Tonight, the doe was demanding an evening snack.

The campground pet was a gentle creature with soft eyes, who had learned that we kept a good supply of her favorite treat: salted crackers. She called every evening at twilight.

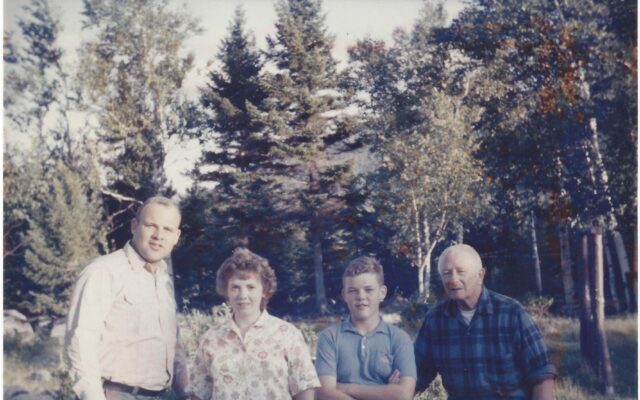

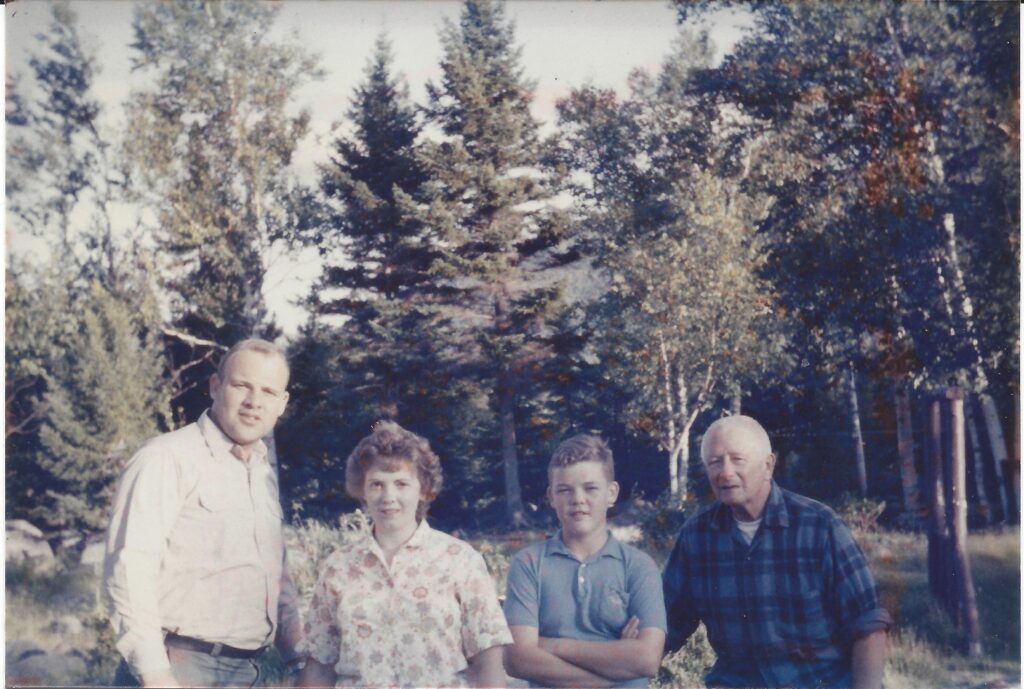

In this 1963 picture taken at Russell Pond, Buzz Caverly is on left and Tim Caverly is third in line.

The second day at camp I busily cleaned campsites, and, yes, that included cleaning one-hole privies. Then there was removing blowdowns from trails, and answering questions from visitors such as, “Where can we see a moose?”

“In the pond,” I answered and pointed to a large bull feeding on watery grass just offshore.

“Where is the best place to catch a brook trout?”

“See that large rock about 100 yards out? Just anchor your canoe beside it. But if there is a caddis fly hatch tonight, fish can be caught anywhere.”

“Will we see bears?” they fretted.

“Could be, but to be safe, don’t leave food scraps around. And certainly, don’t dump bacon grease into the outhouse pit, unless you want an early morning visitor. It’s best to use a rope to tether your food pack from a tree limb, at least 8 feet off the ground. That will keep your goods beyond the reach of scavengers.”

That was the first evening that Grandma didn’t show.

On the third day, Buzz and I built a log rack to secure Grumman canoes against wind gusts. That evening, once again, Grandma didn’t appear for her treat. We wondered if the doe had found better foraging.

When the fourth night arrived, and still no Grandma, we began to worry. “What could have happened? The doe is always here by dusk.” But once again, our hooved friend did not materialize.

When the evening of the fifth day arrived and there was still no sign of Grandma, we began to think the worst. “Maybe she has broken a leg or possibly been attacked by a bear or lynx.” Since this was a time before coyotes were common in the Maine woods, we really didn’t know what could have happened to the four-footed creature.

That night, while preparing supper for guests, I spied a grayish-brown movement by the back window. Grandma had returned. It was time for her crackers. Not wishing to frighten the shy creature with the sounds of cabin conversations, I grabbed a package of saltines and walked down the Roaring Brook Trail and away from camp.

There, I found a comfortable flat piece of granite and sat down. Softly I muttered, “Grandma, crackers are here. Come get one.”

After a second invitation, I heard the snap of a dry twig coming from the other side of the trail. Soon Grandma’s head poked through the branches. Hesitantly, she took a step toward me. I threw the first cracker at her feet, which she immediately scoffed. Moving slightly, I cast the second snack closer to the middle of the trail.

Finally, I offered a third cracker by thumb and forefinger. Grandma, now relaxed, took the treat from my hand with a nuzzle so close I could feel her soft breath. When I opened the waxed sleeve for another cracker, she abruptly turned, and with a flash of her snow-white tail, disappeared. “Now what?” I wondered. “Could a bear, bobcat or some other danger be near?”

Remaining still, I listened for anything that might approach. In a few minutes Grandma quietly reappeared, exposing only her head out of the thicket, to peer up and down the hiking path. When confident that all was safe, she bleated softly and stepped out and off to the side of the hiking route. Behind her appeared a small, brown-reddish coated fawn covered with hundreds of white spots. On wobbly legs he shakily stepped forward to smell my offered cracker. Confident in mom’s protection, a delicate tongue licked the salt from the wafer. Too young to chew, the infant licked the salt from one and then another, experiencing the first treat of his young life.

Five minutes later, mother and son blended back into their forest abode to complete their own supper. From there I walked in deep contemplation about the wonders of the woods to my own accommodations, and to the welcoming smell of pan-fried trout, hash brown potatoes and a new delicacy for me: fresh fiddleheads.

Caverly is a retired Allagash Wilderness Waterway supervisor and has authored 10 books about Maine’s northern forest. For information about his work and to enjoy more North Woods tales, visit allagashtails.com.