In 1918, a pandemic swept through Maine — and offers lessons for containing COVID-19

The death toll started on a Monday — Sept. 23, 1918, to be exact. William Lawry, a 36-year-old Augusta resident, had fallen ill while visiting Camp Devens, an army facility in Massachusetts that had been stricken by influenza, and had returned home a few days earlier to recuperate.

It was too late, though. Lawry became the first Mainer to die from what became known as the Spanish flu, an H1N1 strain of influenza that was unusually virulent and deadly, but the flu had likely been in Maine for at least a week. Over the next eight months, more than 5,000 Maine residents would die during the worst pandemic in modern history — half of them in October 1918 alone.

Just over 100 years later, Maine and the rest of the country are going through another paralyzing pandemic.

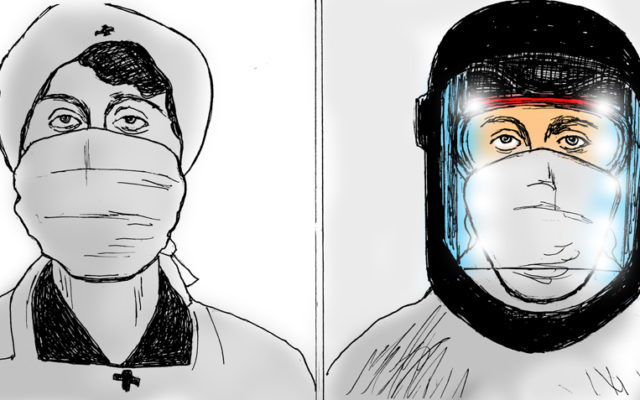

While there’s better tracking this time of the spread of the new coronavirus, more knowledge about how viruses work and a generally more coordinated government response, the two pandemics still have a fair bit in common — from fears of hospitals overcrowding to the methods by which the disease’s spread can be slowed.

Not a Spanish flu

There is much debate among historians and scientists as to where the unique 1918 flu strain originated, though it’s generally believed the first cases occurred in late 1917 or early 1918. Some believe a World War I British army camp in France was the source; others believe it originated somewhere in the Midwest, or possibly in China. Its true origin will likely never be known, unlike today’s coronavirus, which was first identified in late December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei, China.

Regardless, one thing the flu wasn’t was Spanish. Wartime propaganda from both the Allied and Central powers minimized the scope of the illness and mortality rates to maintain morale. Neutral Spain, however, publicized the toll the disease was taking — creating a false impression that Spain was harder hit.

It was the First World War that hastened the spread of the virus around the world. Close quarters in trenches, camps and field hospitals created an ideal scenario for its spread, as did poor sanitation and malnourishment. An initial, less deadly wave of infections occurred in the first half of 1918, but when a second wave with a more virulent strain happened in August of that year, the worldwide death toll was far greater.

In the U.S., the deadly second wave made its first appearance in the Boston area, at the Boston Navy Yard and at Camp Devens. With soldiers and other military personnel constantly moving in and out of those facilities, the flu spread rapidly across New England, as the majority of the 45,000 soldiers being trained at Camp Devens were from New England states, including Maine. It was believed that at least 20 percent of the camp was infected, and family members of those sick flocked to the camp to see their relatives — which only furthered the spread.

A jumbled response

Amid the current pandemic, colleges had started to shift classes online before Maine even had its first confirmed case of COVID-19, much less the first death from the disease.

Within six days of Maine’s first case being identified, schools around the state had closed, restaurants and bars shut down dine-in services, and gatherings of 10 or more were prohibited. Restrictions have since grown more stringent. Individual cities led the way with measures to close down businesses and order residents to stay at home, but the state has followed suit within days.

By contrast, in 1918, government responses were a jumble of conflicting recommendations, even after Maine’s first death from the flu and with cases already numbering in the hundreds. A day-by-day timeline compiled by the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention details some of those responses as they changed over the two months of the disease’s most deadly spread in the state.

In Lewiston, a panel of local physicians believed there was nothing to worry about. The Maine Department of Health issued a warning on Sept. 25, stating that the disease was spread by coughing, sneezing and sharing of utensils and towels. On Sept. 26, the chief of police in Portland said that anti-spitting laws would be strictly enforced.

The first closures of public establishments started on Saturday, Sept. 28 — five days after the Lawry’s death, and with hundreds of known cases in Portland, Brunswick and Bath. The mayor of Portland, Charles Bailey Clarke, called a group of citizens into his office and held a vote on whether to close schools, theaters, dance halls, cinemas and other public gathering places, which they did the following day. Bangor’s city council also voted that weekend to close those facilities, as did Waterville and Augusta.

Still, many resisted. At the state level, Maine’s health commissioner, Leverett D. Bristol, agreed cinemas and theaters should be closed, but balked at a statewide school closure mandate. Lewiston’s board of health continued to deny the presence of the flu in the community, and chose not to close anything. Lewiston’s health commissioner reportedly claimed that closing theaters would be worse than keeping them open, due to the large number of unheated tenements whose residents went to theaters to stay warm.

Nevertheless, on Wednesday, Oct. 2 — nine days after the first death was reported, and with thousands of cases in the state — Lewiston’s city council voted to close schools, theaters and churches. By the end of that week, most of the state had followed suit.

In Bath, a town that nearly doubled in population during World War I to around 20,000 due to increased wartime activity at Bath Iron Works, the disease spread far more rapidly than in other municipalities. Closures and bans on public gatherings didn’t start to take effect until well into October, however, after thousands of people had already been sickened. (BIW, one of the state’s largest employers, is again a focus area during the coronavirus outbreak, with two employees testing positive for the infection while manufacturing operations continue.)

Enforcement of those closures back in 1918 was haphazard. In Portland, there were numerous complaints of beer halls flouting the mandates and staying open, while theaters in the town of Fairfield attracted Waterville residents whose own city’s theaters were closed. Catholic churches also strongly resisted calls to close; the priest at Lewiston’s St. Patrick’s Church refused to call off services on Oct. 7, and stated in a public meeting on Oct. 10 that church services were as essential to society as mills and factories, which were not closed. The decision to close was made for him, however, when Bishop Louis S. Walsh called off services for all churches in the Portland diocese.

Hospitals overrun

With those slow responses to the growing tide of infections, hospitals in Maine quickly became overwhelmed. Major hospitals, including Eastern Maine General Hospital in Bangor and Maine General Hospital in Portland (today called Maine Medical Center), ran out of beds within days, cramming patients into surgical theaters and even refusing to treat some people. In Portland, many of those refused treatment were Irish immigrants, and in response, the Catholic Church opened a new hospital to treat them and others, then called Queen’s Hospital — today known as Northern Light Mercy Hospital.

Many communities statewide had to open satellite locations to treat the sick. The Camden Congregational Church vestry and the old Catholic church on Fore Street in Portland were both converted into emergency hospitals, as was the Oddfellows Hall in Bar Harbor, the Knights of Columbus Hall in Caribou, the Narragansett Hotel in Rockland (today Narragansett Condominiums) and the Bangor Catholic High School for Girls on State Street, today home to grades 4-8 for All Saints’ Catholic School.

Cities and towns across the state also mobilized an army of volunteers, who acted as nurses, distributed food, and transported supplies in what were then still new-fangled automobiles. The Bangor Daily News and the office of Bangor Mayor John Woodman together on Friday, Oct. 18 launched a relief work movement to organize those volunteers, with helpers dispatched to families in need. Similarly, the Courier-Gazette in Rockland printed lists of needed items for the local emergency hospital.

As the disease spread across the state and almost 500 local boards of health responded independently and inconsistently, it became clear that a statewide public health office was needed to coordinate responses to a pandemic like the flu. Bristol, the health commissioner, called for legislation to give the state “full power to handle an epidemic of any kind without interference from a local board.” In 1919, the Maine Legislature placed all municipal health officers and departments under the supervision of the Maine Department of Health — the precursor to today’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention, which is a part of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Though the flu would continue to infect and kill many thousands more over the next six months, by mid-November 1918 — after Armistice Day on Nov. 11, marking the official end of World War I — the numbers began to slow down. With an estimated 47,000 infections, and an estimated statewide population of 777,000 at that time, approximately 6 percent of Mainers were infected — a number that likely understates the true impact, given the unorganized nature of reporting. The state experienced an overall population drop of 2.19 percent between 1917 and 1918.

Lessons from 1918

No one knows how the numbers from today will stack up to 1918. It seems unlikely that deaths will occur on such a massive scale as they did back then, given scientific and medical advancements over the past century, including a better understanding of the nature of viruses, which in 1918 was still quite limited.

Back then, scientists weren’t even sure the flu was caused by a virus at all — that wasn’t proven conclusively until 1933 — and antibiotics to treat subsequent pneumonia infections didn’t exist either. In 1918, there were no tests to give a definitive positive or negative result. Doctors simply assumed patients had it based on their symptoms or contact with other sick people.

Most of the recommendations made today to slow the spread — social distancing, practicing good hygiene and staying isolated if you’re sick — are essentially the same things people did back in 1918, as well as in other pandemics over the centuries. Keeping sick people away from healthy people was standard practice during historic pandemics, even during the Black Death, a plague pandemic in the 14th century.

Though the influenza virus and the coronavirus are different, their methods of transmission and symptoms have a great deal of overlap, with spread caused mostly by respiratory droplets, and fever and cough among the most common symptoms.

The difference today, compared to 1918, is that measures such as closures of public places and social distancing have not only been adopted on a much wider scale, and more rapidly than they were back then, but also that such measures are enforceable at the state level, and not through a hodgepodge of local efforts.

In the first month of the Spanish flu in Maine, thousands of people became sick and hundreds died in all 16 counties. Just over three weeks after the first COVID-19 case was confirmed in Maine, there were 432 confirmed cases and nine deaths as of Friday, with infections reported in 15 out of 16 counties. It remains to be seen if the current pace of infections and deaths stays the same or changes, and it’s not known if the seemingly slower pace in 2020 compared with 1918 is due to better medical care and stricter rules, or if it’s because of the nature of the virus itself — or some combination of everything.

Nevertheless, concerns about hospital overcrowding are just as much a part of the response today as they were back then. In 1918, towns converted churches and hotels into temporary hospitals for the sick and dying when hospitals became overrun in a matter of days. Today, hospitals plead for personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves, for more ventilators to support critically ill patients, and for people to stay home so hospital beds can be free for people sick with COVID-19.

As far as the economic fallout in 1918, compared to today, the data are even more sparse. But there is evidence from the 1918 pandemic that the places in the U.S. that closed schools and banned public gatherings earlier on and for longer periods saw greater employment and economic output in the following year. It remains to be seen what will happen in 2020.

Comparing the 1918 flu and the coronavirus is a tricky thing. But it’s the closest thing we have to another widespread, highly virulent infectious disease making its way through a relatively modern, interconnected society. Using lessons from 1918, we can hope the COVID-19 pandemic won’t be anywhere nearly as devastating.