US Immigration: Lead, follow, or get out of the way

In February 2017, Marco Toninelli boarded a red-eye special plane at Orio al Serio International Airport in Milan, Italy. Landing at Newark Airport in New Jersey, Marco picked up the car he rented ahead of time, and drove three-and-a-half hours through the night, to his pre-booked hotel room in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.

Marco was in the United States to pay his last respects to my mother, Claire M. Fish, at her funeral. Thirty-nine years earlier, in 1978, Marco was an American Field Service (AFS) exchange student who lived with my mother and father in Greenlawn, New York, and attended Harborfields High School. Marco spoke no English. Neither my parents, nor anyone else in my family, spoke Italian.

By the end of the year, Marco was, in spirit, a family member. His English was very good. So was my parents’ conversational Italian. Marco returned to Italy, but stayed in close touch with my family — mostly my parents — over the next four decades. My mom and dad studied Italian until they were able to speak, write, and read Italian. They visited Marco in Italy, loved it, and returning to Italy was one of my mother’s unfulfilled dreams.

Before my parents could get into Italy, Italian authorities questioned them: Why are you here? How long will you be here? Where do you plan to visit? Where will you be staying? How can we get in touch with you?

If my parents had arbitrarily decided to stay an extra week or two without at least notifying Italian authorities — the authorities would have come looking for my parents pretty darn quick. Which is, in part, what a national immigration policy should be.

After his time in Greenlawn, Marco landed a job in Italy with an international company where his English fluency, plus his real life experience with the United States culture, were real advantages. Whenever work brought him to America, Marco would visit or call my parents.

These travel stories with Marco, his family, and my family, are stories of people entering and exiting foreign countries legally. These are positive immigration tales between countries. These legal immigration stories are positive short-term, mid-term, long-term, and economically.

By contrast, the continuing flood of immigrant lawbreakers into the United States is worrisome on all fronts. It is hard for me to list the worrisome parts in order. I’ll start with members of Congress who, in 30-plus years of my lifetime, sanction an American border policy allowing millions of immigrants into this country with no scrutiny. Not the scrutiny Marco had when applying to approval to live and study for one year in the USA. Not the scrutiny my parents received when visiting Marco for two weeks in Italy.

I worry about elected officials sworn to uphold the law, to protect the United States and, when it comes to immigration, do nothing to fix what’s broken. They promise to, and never do.

Worse are elected officials who swear to uphold the nation’s laws, then become de facto lawbreakers by championing illegal immigration systems. Worse still are elected officials who attribute all kinds of negative motivations to American citizens who want an American immigration system that, like the one between my parents and Marco, benefits both countries and immigrants.

The absolute bottom of the worry barrel are elected officials — again, who swore to uphold our laws — whose only action on immigration is to stonewall positive reforms on illegal immigration. We are still a nation of laws, not men. And when men (and women) swear to uphold the laws and don’t, it really is up to to the rest of us to work and vote to replace these corrosive, politicians — sooner rather than later — with honorable men and women.

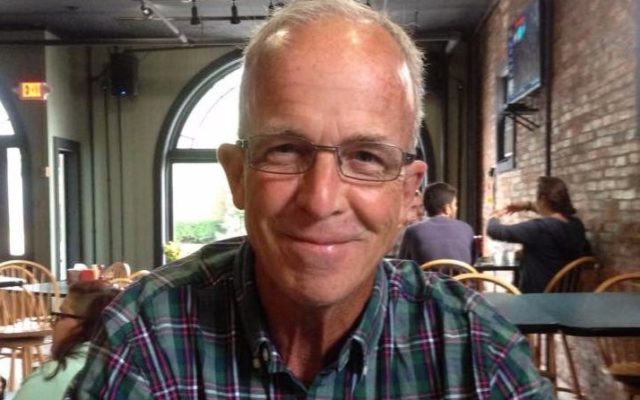

Scott K. Fish has served as a communications staffer for Maine Senate and House Republican caucuses, and was communications director for Senate President Kevin Raye. He founded and edited AsMaineGoes.com and served as director of communications/public relations for Maine’s Department of Corrections until 2015. He is now using his communications skills to serve clients in the private sector.