Life is better if you pursue your passion

All my life I wanted to be either a writer or a musician. At age 18, figuring I didn’t have enough life experience under my belt to write anything worth reading, I refocused most of my energies on becoming a professional musician: someone who earns a living playing music.

I had been smitten by the drums 12 years earlier, but didn’t own my first drum set until I was 18. Before then, I started easing my way into high school garage bands as a lead singer. One of those garage bands — I think we called ourselves “Potter’s Field,” — was hired to play a school dance. Our drummer, Denny, quit the band a few days before the dance, and no one could change his mind.

Finally, Denny said to us, “You can use my drum set, if you want to.” I don’t know what was going on with Denny, but it wasn’t that he wanted to sabotage the band. He just really, really didn’t want to play anymore.

As sorry as I was to see Denny quit, when he offered the use of his silver sparkle Gretsch drum set — I saw an opportunity. “I’ll play drums,” I announced to the other band members. “Well, who’s going to sing lead?” asked Jimmy, the bass guitarist. “I will,” I said. “I’ll do both.”

At that time I had neither sung nor played drums before in public. I knew the basic mechanics of playing drums, but I still had never owned a set. Other than noodling around on friends’ drums for a few minutes, I had never played a full drum set. But I certainly did know the “Potter’s Field” song repertoire.

Probably because not showing up to our school dance was our only other option, the rest of the guys in the band agreed to my idea. We played the dance. I played drums and sang lead. And at the end of the dance a smiling Jimmy gave me a high-five. Success!

Thinking back on all the non-musical jobs I’ve held since (“day gigs”), so I could afford to play music at night and on weekends, I learned much about myself, and about human beings at our best and worst.

Most of those jobs were interesting at first. Early on I discovered it was impossible for me to do the minimum at a “day gig” and then pull out all the stops on the bandstand. It was one or the other. I chose to pull out all the stops wherever I worked.

Jobs where I ran out of stops to pull, or was discouraged from working above-and-beyond? I lost heart and interest in the work and had to move on.

For example, I worked in a Long Island, N.Y. distribution warehouse where magazines and paperbacks were sent out to newsstands and stores; where unsold publications were returned, sorted, wrapped in bundles, dipped in purple ink, and recycled. All day I sorted pallets of magazines into bundles of 25, wrapped them in string, and stacked the bundles on another pallet, which, when full, was hauled away for ink dipping.

A coworker and I decided we’d break the monotony by seeing how many magazines we could sort/bundle/wrap/stack in a workday. We were cranking until confronted by “The Sisters,” two lifelong employees at the warehouse who said, “You’re making us all look bad. If you want to keep your jobs — slow down!”

Today online “personality tests” help people figure out which jobs best suit them.

Working bandstands and “day gigs” taught me that, if all the world’s a stage, I’m best suited for life’s mysteries and working without a safety net.

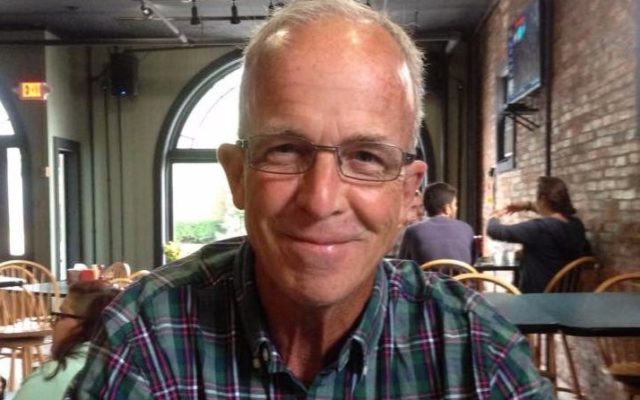

Scott K. Fish has served as a communications staffer for Maine Senate and House Republican caucuses, and was communications director for Senate President Kevin Raye. He founded and edited AsMaineGoes.com and served as director of communications/public relations for Maine’s Department of Corrections until 2015. He is now using his communications skills to serve clients in the private sector.