Jack knows there are angels among us

Jack, about six feet tall, thin, wearing baggy blue jeans and gray t-shirt, stepped from his company van. With dark circles around his eyes, a left eye that drifted slightly, and chin length light brown hair, Jack resembled television actor David Carradine (Kung Fu).

An electrical job estimator, Jack was on time for his appointment. My girlfriend, Eileen, was considering electrical modifications to her “fixer upper” home in Florida. Most of the year we live and work in Maine.

“Hi, Jack. I’m Eileen,” she said, reaching out her hand.

“Hi Eileen,” Jack replied. “I’m not going to shake your hand.”

Examining his right hand, he explained, “I have a cut on my hand. I’m trying to give it some open air. But, hi, Eileen. I’m glad to meet you.”

Inside, Jack went room to room, listening to Eileen’s modification plans, making suggestions, writing on his order pad in its gray metal case.

Jack had lived for a while in New Hampshire. After serving in the U.S. Air Force as a B-52 tail gunner, Jack decided to hike the Appalachian Trail, Georgia to Maine, in one trip.

An Air Force buddy backed out at the “very last minute” on hiking with Jack, so Jack hiked alone. The experience, he said, centered him, helped him figure out what to do next with his life.

Moving to Florida, he apprenticed with an electrician, learned, then practiced, the trade, and now works for the company as a job estimator.

Jack was excited to show us photos on his iPhone of his recent trip to Fenway Park for a Red Sox vs. Yankees game.

“The Red Sox are my team,” he said. “I was sitting three seats behind home plate. Normally, somebody has to die to get those seats.”

“Who’d you kill?” laughed Eileen.

“Well,” said Jack, “the whole trip was a gift. I have a terminal illness.”

Without giving specifics, it was clear seeing the Red Sox playing the Yankees at Fenway was a lifelong dream some entity fulfilled.

At age 50, Jack found out he has a rare genetic disease deteriorating his lungs and liver. Each week he receives an intravenous transfusion of blood plasma which buys time. “Most people,” he said, “have never heard of my disease.”

“I know exactly what you have,” said Eileen. “You have Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. I used to work in a clinic that treats Alpha-1 patients. It’s a genetic disease passed from parents to their children.”

Jack’s whole demeanor brightened. “Yes,” he answered Eileen. “This is so great meeting you. Most people don’t know about Alpha-1.”

Compound a terminal diagnosis with the inability to speak about it with most people, I could understand how finding someone to communicate with would be a boost.

Eventually, Alpha-1 patients need lung and/or liver transplants or they die. Eileen told Jack of an Alpha 1 friend who had a lung transplant “at the last minute” and “looks great.”

Jack nodded. There are levels of care available, he said, when he’s lost 90-percent of his lung capacity. He’s lost 80-percent lung capacity, and still works full-time.

“I pay taxes. I pull my own weight,” he said, frustrated, but not bitter, the increased level of care is not available now.

With two adult children out on their own, Jack and his wife — because “it seemed the right thing to do” — recently chose to take in the 3- and 5-year old children of a young relative, a mom, dead from ovarian cancer.

“Don’t lose hope,” Eileen said, as Jack was leaving. “There are angels among us watching over us,” she said.

“Oh,” said Jack, “I know there are.”

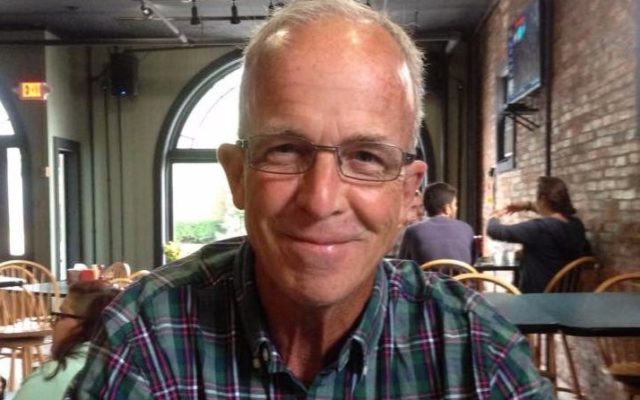

Scott K. Fish has served as a communications staffer for Maine Senate and House Republican caucuses, and was communications director for Senate President Kevin Raye. He founded and edited AsMaineGoes.com and served as director of communications/public relations for Maine’s Department of Corrections until 2015. He is now using his communications skills to serve clients in the private sector.