Historical photos prove that baseball springs eternal in Maine

By Troy R. Bennett, Bangor Daily News Staff

In 1845, the Knickerbocker Club of New York City began using the Elysian Fields across the Hudson River in Hoboken, New Jersey, to play baseball due to the lack of suitable grounds on Manhattan Island.

The next year, the Knickerbockers faced the New York Nine there in what’s remembered as the first organized baseball game between two clubs.

The Pine Tree State was not too far behind.

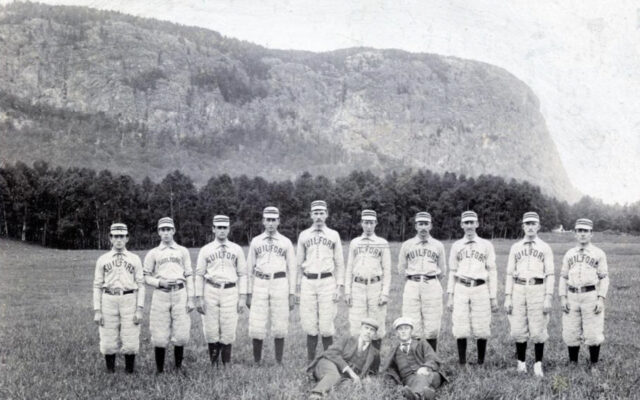

1895 TEAM — The Guilford town baseball team poses for a photo in front of Mount Kineo on August 29, 1895. From left are Louis Gilbert, Plummer Chadbourne, Frank Martin, Alton Chadbourne, Carlyle Hussey, Leland Ross, Forest Rowell, James Hudson, Arthur Witham, Harry Katen, sitting are Charles Turner and Charles Little, the manager.

According to Maine baseball historian and author Will Anderson, the first documented game here took place on October 10, 1860. On that day, as noted in the local paper, Brunswick’s Sunrise Club took on the senior class team from Bowdoin College, across the Androscoggin River, at the Topsham Fairgrounds.

The Sunrise Club beat Bowdoin 46-42 in a game where pitching and defense apparently played no part. The Brunswick Telegraph newspaper even published a box score for the game, still decipherable, 163 years later.

Nearly concurrent to the rise of baseball was the advent and spread of photography, invented in 1829. By the time the Bowdoin and Sunrise clubs took to the diamond at the fairgrounds pictures were cheap and easy — thanks to the newly invented tintype process.

Though no known photos have surfaced of that fateful game, other baseball photos soon followed. Historic Maine picture collections are brimming with images of both kids and adults enjoying what came to be known as the national pastime.

Four years after Bowdoin lost to the local team, the team played Harvard in Portland on the 4th of July. That contest was trumpeted in newspapers across the state from Bangor to Portland.

Unfortunately, they lost again, 13-40.

“The Harvard boys won chiefly on their rapid pitching and skillful catching,” read a piece in Portland’s Eastern Argus newspaper. “The Bowdoin students have been accustomed to playing with a slow pitch, and when the ball came to them as if sped from a parrot gun, it completely upset their calculations.”

Loss aside, the Argus reported a few days later that the game was such a success that it had “aroused the interest of our young men in this fine sport” and local teams were being organized. Soon, as in the rest of the United States, teams were springing up all over Maine.

By the 20th century nearly every Maine school, town, mill and factory had an organized ball team — and lots of non-professionals had cameras, too, thanks to the ubiquitous Kodak Brownie camera, released in 1900.

“You press the button, we do the rest,” read ads for the unassuming black, boxlike cameras.

1925 BASEBALL GAME — Two baseball teams face off at the Guilford Athletic Field in a 1925 photograph which includes an impressive, wooden grandstand behind home plate. Later, bleachers were added down the left field foul line. The field is still there, as well as the Preble Farm, seen in the background, which is now home to Guilford Hardware.

One 1925 photograph, which may have been made with a Brownie, shows an impressive, wooden grandstand behind home plate at a ballfield in Guilford. Another shows a Guilford team posing in front of Mount Kineo around the turn of the century.

Around that time, eventual major-leaguer Chester “Chet” Chadbourne was playing for the Piscataquis County milltown’s local team. Chadbournes’s brothers, Plummer and Alton, appear in the Kineo team photo.

A stunning, 1899 professional portrait from Belfast shows a relaxed and confident looking local team bearing the letter “B” on their uniforms. The team was racially integrated with African-American player Fred Johnson sitting on the left. White teammate Orrie Vickery stands behind Johnson with his hand draped over his shoulder in what looks like a gesture of camaraderie.

In the Mantor Library collection at the University of Maine at Farmington is a photo postcard which may show an early women’s baseball team, circa 1897. The women are dressed in matching blouses and skirts. Some wear baseball caps and hold bats. One woman looks poised to throw a baseball.

A short poem graces the back of the postcard reading, “Is this a good ball team? Is it? Well I guess! Did you ever see anything slow that came from the F.N.S.”

The initials stand for Farmington Normal School, as the institution was then called.

One interesting bit of non-photographic baseball ephemera found at the Maine Historical Society is a hand-painted invitation from one team challenging another to a rematch.

The paper item was issued by the Murphy Balsam team of Portland, owned by a local pharmacist, and directed at a team tied to the Poland Spring Resort.

“This time we know we can beat you,” it reads.

At the time, Poland Springs’ pitcher, Ralph Plaisted, along with two teammates, left the team. A local newspaper reported that the cause was either drunkenness or defection to another team.

The Balsam’s invitation jabs at this sore spot by picturing a cracked water pitcher with Plaisted’s name on it.

The team’s had faced each other on both July 21 and 28. Portland apparently lost both games. The invitation did the trick and Portland and Poland Spring met again on Sept. 5.

It didn’t end with a Portland victory, however, as Portland’s Evening Express newspaper reported.

“It was an exciting game,” read a page eight account, “but was called at the end of the seventh inning to allow the Balsams to catch a train.”

The game ended in a 16-16 tie.