More than 170-year-old Dover-Foxcroft church plans to become carbon neutral

DOVER-FOXCROFT — The Rev. Stephen “Steve” Hastings of Dover-Foxcroft Congregational Church picked up a tarnished door handle, and it turned over in his hands — the only surviving relic from the congregation’s first meeting place.

A fire destroyed the church building on Lincoln Street one Jan. 15, 1835, the day after it was dedicated, Hastings said. The congregation’s next church on North Street burned down Oct. 21, 1850. The third, built on West Main Street, was dedicated Oct. 22, 1851, has undergone many changes but still stands today.

It’s where the church will celebrate 200 years with a series of events throughout the year, including a potluck in February, an outdoor worship service at Peaks-Kenny State Park this summer and other activities. The congregation believes its first service was on Jan. 1, 1823, Hastings said.

ONLY SURVIVING RELIC — Pastor Stephen “Steve” Hastings of the Dover-Foxcroft Congregational Church holds a tarnished door handle, the only surviving relic from the congregation’s first meeting place on Lincoln Street, which burned down on its dedication day in 1835.

Modern improvements are taking place in the historic church as it prepares for the next century, including the installation of a solar panel array on the roof and other efforts to eliminate its carbon footprint to combat climate change. Leaders are also seeking ways to stay relevant in one of the least religious states in the nation, and as small communities are forced to confront global issues.

Hastings, who has served churches in Winthrop, Kennebunk, Leeds and Hartford, has a doctorate in environmental ethics and spirituality, an interest that had a lot to do with his decision to enter the ministry in 1990.

“This congregation is very interested in the world around them and how faith speaks to that,” Hastings said. “There’s a general openness to talking about issues. We’re very much on a journey, open to new things and new ways of understanding the past and how faith has to be here and now. Sometimes that’s challenging.”

CHURCH TODAY — The Dover-Foxcroft Congregational Church, which just celebrated 200 years, is pictured after a fresh snowfall on Jan. 5.

It means the church community must be open to growth — not just in numbers, but in its perception of people and willingness to revisit beliefs to see how they fit into today’s society, said Hastings, who has been pastor since 2017.

The church’s decision to declare itself as open and affirming to all people in 2018 is a big part of that, he said.

Members see key issues, like environmental concerns, as more central, rather than peripheral, to church life, the pastor said. That’s why the church has launched an $80,000 capital campaign to achieve carbon neutrality by 2023.

CHURCH MEMORABILIA — Pastor Stephen “Steve” Hastings talks about the Dover-Foxcroft Congregational Church’s rich history on Wednesday, Jan. 4. In honor of the congregation turning 200 years old, historic photographs and memorabilia are on display.

Last year it spent $22,000 to add heat pumps to the parsonage — the pastor’s house owned by the church — and increased ceiling insulation throughout the church for another $22,000. Sundog Solar, based in Searsport, will install a $133,800 solar panel array on the roof in March, which should generate enough electricity to cover the church and parsonage, plus cut down on expenses for the next 30 years.

There also are plans to install more heat pumps in the church, a pellet boiler or a combination of the two to eliminate or substantially reduce the use of heating oil, according to information the church provided.

The church — known locally for its striking steeple and clock — functions as a community center in many ways. The Center Theatre, for example, has relied on it for practice space, and organizations or resident volunteers use the kitchen to prepare dinners each Monday. The effort began as a free, in-person dinner to feed the town’s food-insecure families, but transitioned to take-out meals during the pandemic, Hastings said.

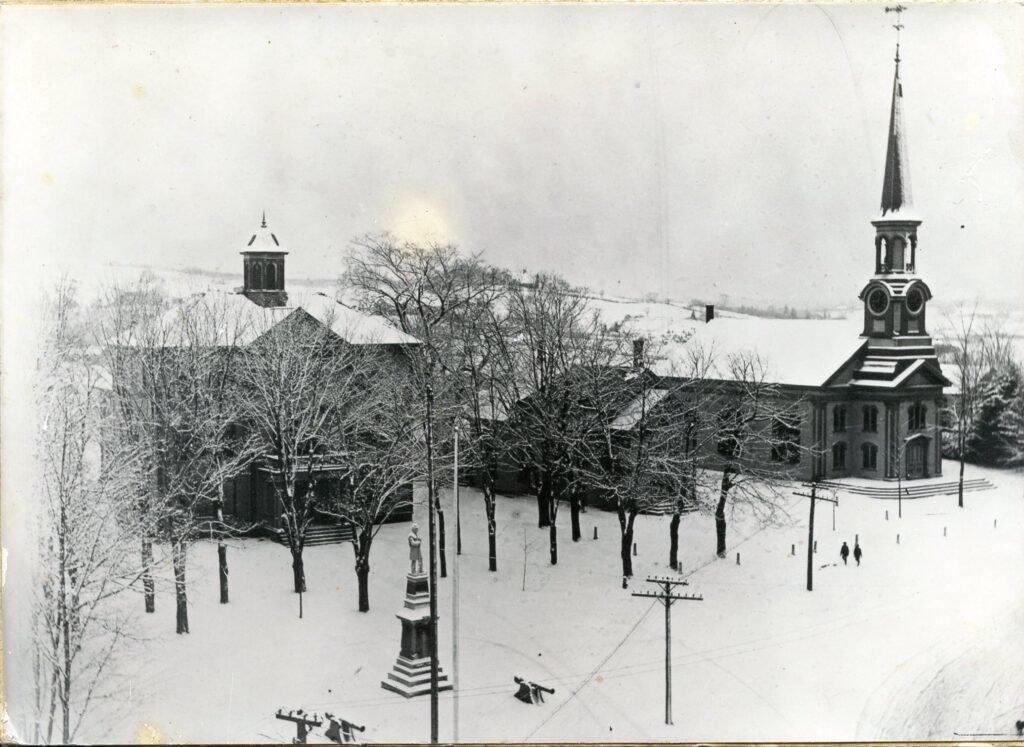

MONUMENT SQUARE — An undated photograph shows Monument Square and, at left, a church known today as the Dover-Foxcroft Congregational Church.

A medical lending closet loans wheelchairs, walkers, hospital beds and other necessities to community members, said Jan Barton, who helps run the program and has been involved with the church for about 20 years, along with her husband, George.

The church held its first Christmas fair and quarter store for kids last month, where all items were 25 cents. Area children decided to donate the more than $500 raised to Penquis Animal Welfare Sanctuary, or PAWS, in Milo.

“It’s hard for me to put my finger on just one thing that makes the church special,” Barton said. “It’s just very open and available to anybody.”

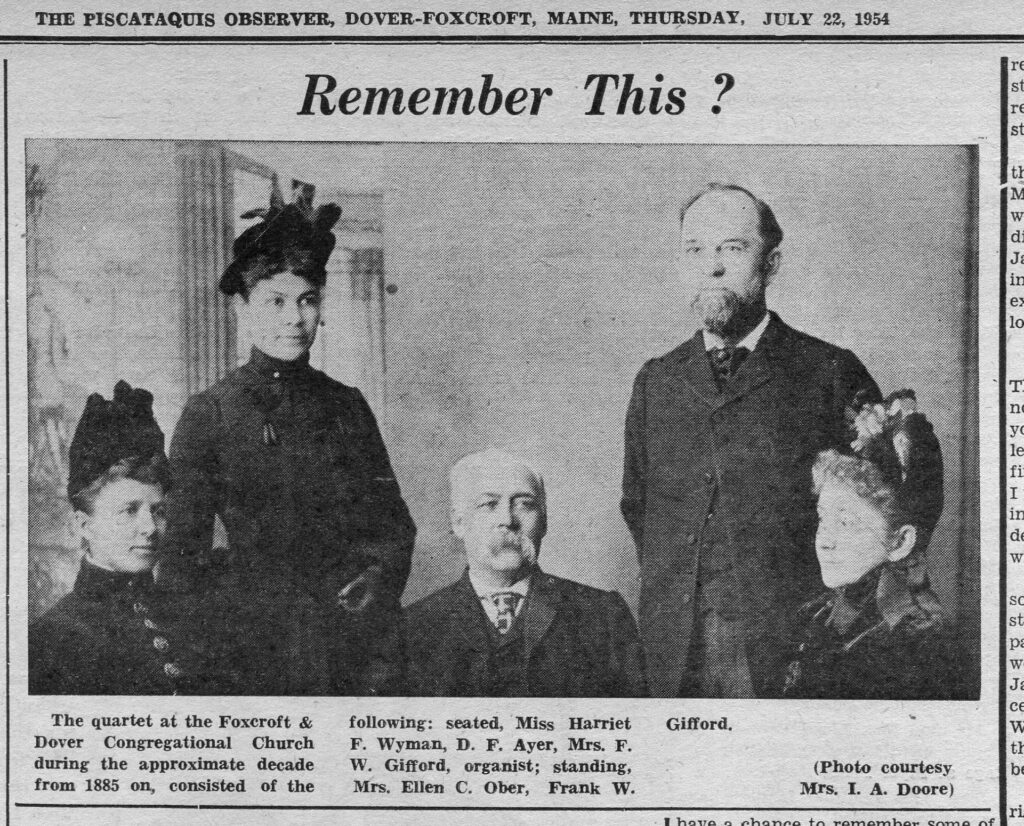

FOXCROFT & DOVER CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH — A news clipping from the Piscataquis Observer shows the quartet at the Dover-Foxcroft Congregational Church in about 1885. At the time, the church was known as the Foxcroft & Dover Congregational Church.

Student Pastor Rachel Dobbs is experimenting with Messy Church, an effort to reach young people or those who don’t have a tradition of church life. It’s an informal gathering held once a month on a Saturday — “messy, so to speak,” Hastings said — where people are welcome to play games and do crafts, enjoy dinner and worship.

Through its history, the church, which has had different names over the years, has maintained a relationship with the town, which didn’t become Dover-Foxcroft until March 1922, after five attempts to merge.

Many of the town’s founders and wealthy residents — C.H.B. Woodbury, Silas Paul, members of the Mayo family and others — supported the church and funded improvements over the decades, said Chris Maas, a director at the Dover-Foxcroft Historical Society.

CHURCHGOERS ON THEIR WAY — An undated photograph shows churchgoers making their way to the Dover-Foxcroft Congregational Church, which has held different names throughout its long history.

“Think about it. In 1899, Woodbury walked from one end of town [Dover], past three other churches to get to the congregational church in Foxcroft,” Maas said. “Influential people throughout history were members of that church.”

Hastings considers the clock, added in 1966 and owned by the town, to be a fascinating work of craftsmanship. Once mechanical and run by huge weights, the clock’s hammer mechanism would strike the bell every hour, he said.

Until 20 years ago, members of the church would have to go up to the steeple once a week and wind up the weights that ran it, he said. The system was eventually disconnected and replaced with loudspeakers.

“The bicentennial allows us to look back at the history, but we try to balance that with the notion that this is the doorway to a new century,” Hastings said.

The Dover-Foxcroft Congregational Church, at right, is pictured in this undated historic photograph.

PASTOR HASTINGS — Pastor Stephen “Steve” Hastings has been senior minister at the Dover-Foxcroft Congregational Church since August 2017.