Many of us could use a civics lesson

An old friend from the wonderful world of public policy emailed me last week with information about an “important” upcoming U.S. Senate vote on “forced arbitration.” And sitting by myself, reading my friend’s email, I felt my shoulders droop a little, and I shook my head side-to-side.

I imagine myself onstage in an old theater asking 20 strangers seated before me, “Who can tell me what forced arbitration is?” I’d be surprised — unless one of the strangers is in a legal profession — if any of them can define forced arbitration.

To be honest, after reading my friend’s email, I went online and looked up “forced arbitration” just to be sure I understood what I was reading. Public policy, politics, law — each of these affect our lives, for good or bad, every day. A key part of my job working as a communications staffer in the Maine Legislature was understanding the foreign language of law making, and translating it into plain English so the reading public could understand it too.

Which raises a good question: Shouldn’t the average voting age citizen be at least conversant in the language of public policy, politics, and law? Of course. Not too long ago U.S. public schools taught students, starting in grade school, the language of public policy, politics, and law. That language is called civics. Then, for the last few generations, we stopped.

We became a nation where many of us, perhaps most of us, graduated high school without ever taking a civics class. That’s certainly true in my case. I was about 33 years old, four or five years after I was working for the Maine Legislature, when I discovered Maine grade school civics textbooks in a Hallowell used bookstore.

Based on reading those civics schoolbooks, and my experience with legislators, I had the personally troubling realization that, with few exceptions, we are a state of voters who don’t know how government works (civics), electing people who don’t know how government works (civics), to make our laws.

The blind leading the blind.

Some days it seems other people and organizations have spotted this civics void and the nation is slowly heading in the right direction. But, it’s said, men do not turn sharp corners. So, until we are a nation of people once again conversant in civics there will be a role for public policy translators.

My friend contacted me about this upcoming U.S. Senate vote on what is officially Senate Joint Resolution 47:

S.J.Res.47 – A joint resolution providing for congressional disapproval under chapter 8 of title 5, United States Code, of the rule submitted by Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection relating to “Arbitration Agreements.”

At its core, this is about a federal Consumer Financial Protection Board rule. If the rule stands, individuals harmed, for example, by the personal information hacking at Equifax, retain their right to ask for their day in court in a manner they choose.

If the Senate votes no, forced arbitration is your likely recourse where. That is, in this example, Equifax will decide in what manner, if at all, you can sue them.

It’s hard to argue against the notion that the language of politics, public policy, and law keeps citizens it’s meant to serve at a distance. If so, we really have ourselves to blame. In our system of government, we, the people, choose our elected officials, sending them to Washington to represent us.

If our elected officials are truly going to represent us, don’t you think we ought to be able to understand one another?

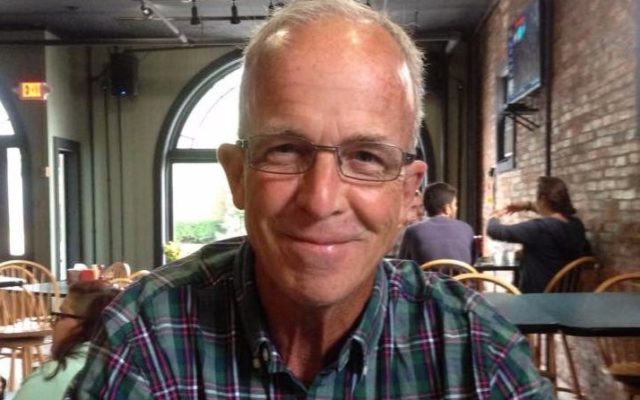

Scott K. Fish has served as a communications staffer for Maine Senate and House Republican caucuses, and was communications director for Senate President Kevin Raye. He founded and edited AsMaineGoes.com and served as director of communications/public relations for Maine’s Department of Corrections until 2015. He is now using his communications skills to serve clients in the private sector.