Here are some things you probably didn’t know about Maine owls

By Bob Duchesne

Someday I may write a book containing everything I don’t know about birds. I expect it will be at least a three-volume set. So, when the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife offered a Zoom presentation on owls two weeks ago, two lines in the description caught my immediate attention. “What we know about Maine’s owls … What is still a mystery.”

Thus intrigued, I was one of the 189 people who tuned in to watch. What could I learn, and what could I steal that I could pass on to you?

Let’s start with the basics. There are three common owls nesting in Maine; great horned owl, barred owl and northern saw-whet owl. There are three rare ones nesting here sporadically; short-eared owl, long-eared owl and eastern screech owl. There is one rare owl that theoretically breeds here, but we’ve never found confirming evidence: boreal owl. Plus, there are three occasional winter visitors that nest far north of Maine: snowy owl, great gray owl and northern hawk-owl.

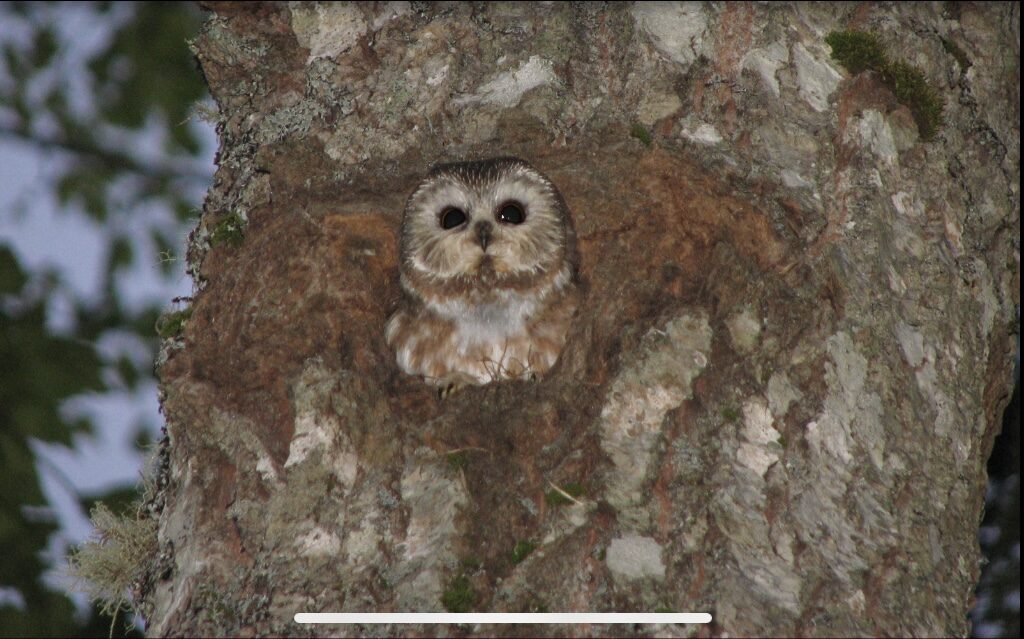

SAW-WHET OWL – This northern saw-whet owl almost appears to be part of the tree in which it is nesting.

A few snowy owls winter in the state every year. A great gray owl or northern hawk-owl wanders into the state about once every four years or so.

There are a few records of short-eared and long-eared owls breeding in Maine. The former likes big, open areas, such as grassy marshes. The latter is a secretive forest owl. Aroostook County’s Bill Sheehan found one nesting in Presque Isle in 2016 but, as I’ve explained in a previous column, Bill sees everything.

Eastern screech owls are undoubtedly moving across the New Hampshire border. No nest has been confirmed yet, but increasing numbers have been heard in eastern York and Cumberland Counties over the last several years.

And then there is the boreal owl. Longtime readers may know that this is my most coveted bird. It’s the bird I most want to see before I die, which I suppose means I shouldn’t be in a rush. It nests in conifer forests across Canada and down the western Rocky Mountains. It might even nest in Maine’s northern forest, but so few people bird there that nobody really knows. That could change.

Wildlife biologists have conducted owl studies over the years, mostly under the auspices of Maine Audubon. But the DIF&W’s Maine Bird Atlas project is making a concerted effort to find the rare ones. Experts will fan out into likely areas and try to locate some. You know I’ll be looking for boreal owls.

Atlas volunteers will also be on the lookout for the common owls. Here are some of those tidbits I stole from the presentation.

All owls nest early, often when there is still snow on the ground. Courtship starts as early as January, and nesting may be underway by March for some species, especially great horned owls. That’s convenient, because great horned owls nest in the open, often taking over the nests of other big birds, such as ospreys, great blue herons and red-tailed hawks.

Since owls nest earlier than the hawks, they commandeer the nest before the hawk returns. But the hawk may have two nest sites, and uses whichever one the owl doesn’t steal. Clever, these birds.

Something I didn’t know before: Great horned owls will steal a raven’s nest, which is typically on a cliff face. Oh, wow, really?

I knew barred owls were cavity-nesters. I didn’t know they will use a properly sized nest box. Now I do. Northern saw-whet owls will also use a nest box. I put a saw-whet box out behind my house 20 years ago. It remains untouched.

I already knew that rare winter owls aren’t necessarily starving. For a long time, biologists assumed that snowy owls were forced into Maine by hunger. But after examining owls that were injured or captured for purposes of relocation — away from airports, for instance — we’ve come to realize that owls come down in winter following a plentiful summer supply of rodents, especially lemmings. When so many well-fed snowy owl chicks thrive in summer, they need to spread out to find food in winter.

I learned that I need to train my ear. I’m familiar with the typical hoots of Maine’s resident owls. I am unfamiliar with the many other noises they make, especially youngsters begging for food. I’ve only recently learned of the calls northern saw-whet owls make, and that has helped me find a few.

So all this is going on, now or soon. Best thing you can do; if you know of a nesting owl, tell the DIF&W.