A Maine tourism hotspot hopes new housing project will revive its middle class

GREENVILLE — Greenville’s town leaders and businesses hope a proposed housing development will bring a much-needed economic boost to an area that has struggled to attract and retain workers because of its limited housing stock.

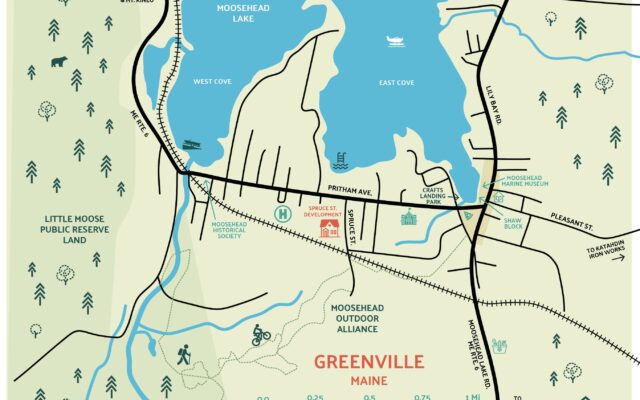

The Northern Forest Center last week announced it bought a 5-acre parcel off Spruce Street where it will build a 29-unit housing development, including a mix of multi-family buildings, duplexes and single-family homes, over the next three years. It is designed to provide the “missing-middle housing” that will enable families to invest in the town and “build the sustainability of the Moosehead Lake region’s year-round economy,” Director Mike Wilson said.

The local hospital, an inn owner and others said May 15 they see the development, estimated to cost $11.5 million, as a step to alleviating the lack of affordable housing in town. They hope it helps employers fill vacancies and gives prospective workers more reasonably priced options. The development has the potential to inject new energy into Greenville and draw young families to grow the school’s population, they said.

“We have this vast outdoor playground that is really attractive to young workers and families. I talk to people who want to move here, but if you can’t provide housing, you hit a dead end,” said Jenn Whitlow, owner of the Blair Hill Inn.

Whitlow has had to provide housing for her employees since she bought the inn two years ago. She spent days calling owners of short-term rentals to get six-month and year-long leases at three houses in town, where eight of her roughly 30 employees live. Some contribute partially toward rent, but Whitlow covers the expenses for many because it’s a more affordable arrangement for them, she said.

When Whitlow’s spa manager wanted to buy a house in Greenville and couldn’t find one, she offered her the apartment on the inn’s property. She didn’t want to lose someone whose experience has boosted the offerings and professionalism of the spa, she said.

“When you don’t have the talent locally for some of these speciality roles, you have to bring people in and give them housing,” she said.

Whitlow imagines she will always have to provide housing because it makes the job more enticing, especially for seasonal workers. Some of her employees are local, while others are from outside the state and country.

Once the development is built, however, she will look to rent there and sponsor the applications of employees interested in living there, she said.

One of Greenville’s major employers, Northern Light CA Dean Hospital, supports the Northern Forest Center efforts because housing is a barrier to recruiting and retaining staffers. Traveling nurses, for instance, find it a challenge to find temporary housing, a hospital spokesperson said.

“Some employees face long commute times. Others choose housing in or near Greenville that doesn’t completely meet their needs because of the low inventory of affordable local housing,” said Marie Vienneau, the hospital’s president.

Whitlow knows people who live in Greenville’s low-income housing developments “who are gainfully employed and ready to step out of that,” she said, but there are no realistic options for them. She hopes this new development can give them that opportunity, she said.

It might also be interesting to seniors who own homes and wish to scale back, said Margarita Contreni, president of the Moosehead Lake Regional Economic Development Corp.

The group had plans to bring single-family homes to the land off Spruce Street but sold it to the Northern Forest Center because it couldn’t find a developer who could do it “within our financial targets,” she said, adding that prices only rose with the COVID-19 pandemic and inflation.

The Northern Forest Center is the right group to execute the project because it has brought middle-income housing to Millinocket and communities in other states, Contreni said.

The Greenville development will be the group’s sixth housing project and the first to be built from the ground up. The center has previously developed housing in Millinocket and in New Hampshire, with other projects planned in Bethel, Maine; St. Johnsbury, Vermont; and Tupper Lake, New York.