50 years ago, Stephen King’s ‘Carrie’ changed literature — and Maine

By Emily Burnham, Bangor Daily News Staff

Paul and Melissa Stearns both remember the day they found out that Mr. King sold “Carrie,” his first novel, to a publisher.

It was spring 1973. They were both seniors in Stephen King’s fantasy and science fiction class at Hampden Academy, an elective where, as Paul Stearns said, he and Melissa, his future wife, began to fall in love while reading classics like “Dracula” and “Fahrenheit 451.”

Paul Stearns said Mr. King walked into class with a big grin on his face, and told his students he’d sold “Carrie” to Doubleday for a tidy sum of money.

“We all went ‘Oh, yeah right, sure you did.’” Stearns said, now retired after serving as superintendent of SAD #4 in Guilford, and as a Republican state representative. “Sure enough, a few days later, Mr. King drives up to school in a new car. And we all said, ‘Boy, I guess he was telling the truth.’ Little did we know how big it was all going to get.”

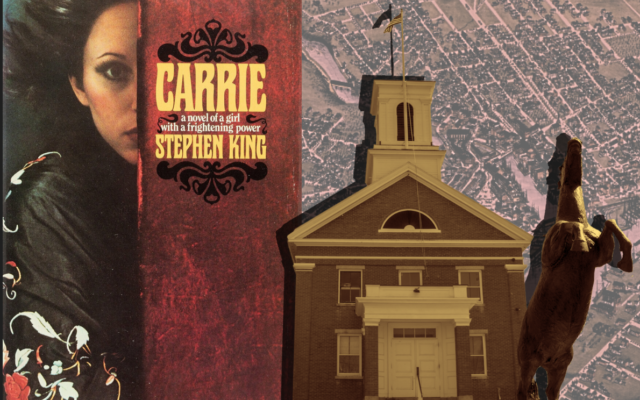

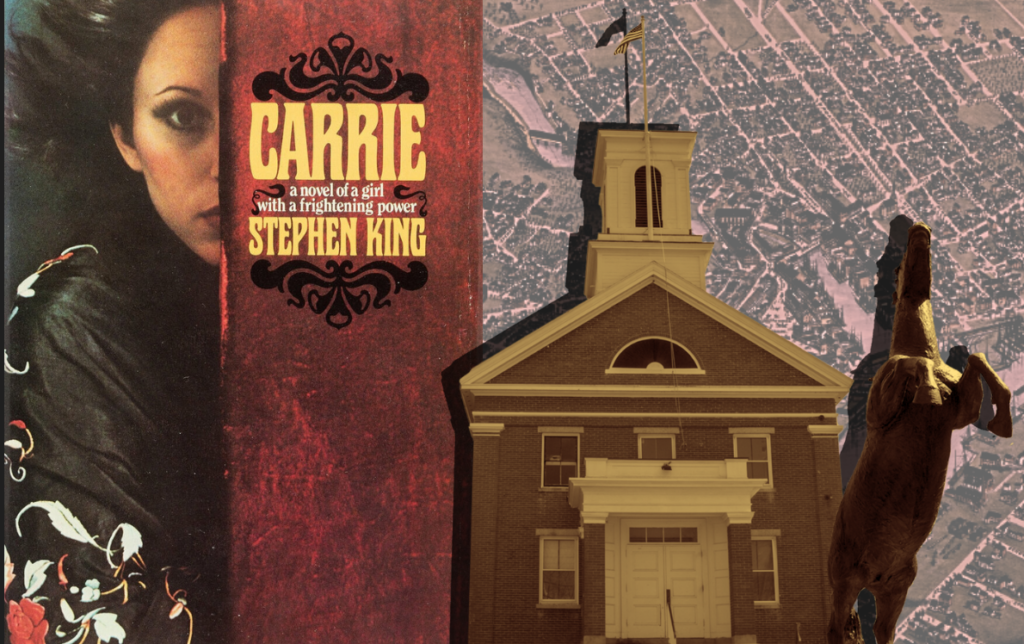

‘CARRIE’ — Published 50 years ago, Stephen King’s debut novel “Carrie” revolutionized the horror genre and permanently altered the perception of Maine. Pictured is the cover of “Carrie,” Hampden Academy and a map of Bangor.

Friday marks 50 years since King’s debut novel was published on April 5, 1974. “Carrie” was an instant bestseller that catapulted King to international fame and revolutionized the horror genre, with its savagely realistic depiction of a bullied teen who harbors secret telekinetic powers.

For Maria Thibodeau, who was also a student of King’s at Hampden Academy, she was simply happy for her teacher, who she said everybody liked. King was 25 at the time, not much older than his students, and had an easy way of connecting with them.

“He was a very good teacher who genuinely cared for his students. He came into class that day in the old suit jacket that Mr. McCutcheon had given him to wear,” Thibodeau said, referring to Everett McCutcheon, a fellow English teacher and mentor to King. “He was all smiles, from ear to ear. We were all really happy for him.”

“Carrie” changed King’s life, of course, but it also changed the way Mainers — and folks in the Bangor area, in particular — saw themselves.

Here was a newly minted literary superstar that we could call our own. Not someone that came from wealth, either, or from an elite school. King grew up as a regular kid, in a regular Maine town, with a regular job, scraping by to make ends meet and using his talent and determination to do something extraordinary.

And later on, after hundreds of millions of books and movie tickets sold, the Kings put most of their money into philanthropic efforts, funding public libraries, fire departments, youth sports and worthy nonprofits all over the state. That’s something for Mainers to be inspired by.

King didn’t start developing the character of Carrie White until he’d started teaching at Hampden Academy. It’s hard not to imagine that taking a daily dive into the heady stew of teenage hormones at a high school had an influence on his choice of subject matter, though King said in his 2000 memoir “On Writing” that he was inspired by two bullied girls he remembered from his own high school days.

Stephen and Tabitha King and their two young children, Joe and Naomi — Owen wasn’t born yet — were living in a trailer in Hermon. King roughed out a draft of the story that he later tossed in the trash with disgust. As the story famously goes, Tabitha King fished the crumpled up papers out of the garbage and told her husband to try again. Without Tabby, there is no Steve.

Carrie White — like future King heroes and villains like Pennywise, Annie Wilkes, Jack Torrance, Andy Dufresne and countless others — became permanently lodged in pop culture.

A character like Carrie is a villain, yes, but one that’s difficult to fully loathe — it’s hard not to feel a twinge of malevolent relief when she unleashes her wrath upon a school that’s treated her like dirt, and a mother who has abused her since birth. She’s complicated, just like life.

The book was set in Maine, but a Maine that most readers never encountered in literature. The Maine most people know was one of rocky coasts, rugged mountains and endless trees — the sort of place that Edna St. Vincent Millay poeticized, Henry David Thoreau used to symbolize the perfection of nature and Andrew Wyeth and Winslow Homer painted. It’s Vacationland. It’s perfect.

Despite its fantastical elements, King’s Maine is closer to reality. Its seemingly placid exterior barely contains an interior rife with secrets, mystery, shadows and even violence. It’s full of ordinary people, forced to do extraordinary things. And monsters, lurking in shops and sewers and creaky old homes — and in the halls of politics and commerce — in forgotten towns far away from the polished-up tourist communities. It’s the Maine King grew up in, and one that most of us know all too well.

King himself told the Bangor Daily News in 1977 that the average person — from Maine, or from anywhere, really — said that the monsters in his books aren’t what scares people. What truly scares them is reality.

“People aren’t really afraid of vampires. What they are afraid of is their own death. Or the oil bill,” he told the BDN. “When they are reading and watching my stories, they are not afraid of the oil bill, I’ll tell you.”

King visits many places and universes in his works: the icy foreboding of Colorado, the endless expanse of the plains of the Midwest, the volatile beaches of Florida. He creates monsters out of the mist. He takes everyday things like cars and pets and phones and makes them instruments of terror. He sees dignity and beauty in a prison inmate, and plants a rose at the nexus of a universe that could at any moment collapse into chaos.

But it is Maine where it all started 50 years ago, with a powerful teenage girl dreamed up in front of a typewriter in the Bangor area. And it’s where King returns to again and again, in a fantastic story that still is being written.