History of the Moir Farm

By Trevor O’Leary

Ranger, Allagash Wilderness Waterway

TOWNSHIP 15, RANGE 11 — One mile downstream from Michaud farm, the last ranger station on the Allagash Wilderness Waterway, there sits an old farmstead that was settled in the mid-1800s by the Moir family. George Moir settled a large piece of land two miles upstream of the Allagash Falls on the South bank of the river, which also included all the islands from Finley Bogan downstream to the Allagash Falls. George had with him his wife, Lucinda (Diamond) Moir, who along with her three sisters, were instrumental in settling the town of Allagash.

Contributed photo

Contributed photo

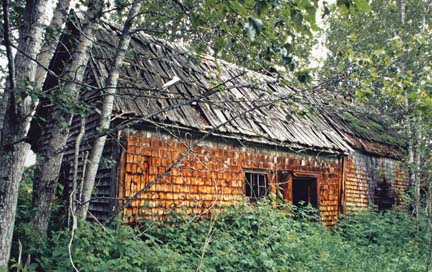

HISTORIC HOME ON THE ALLAGASH — In the early 1900s, Henry Taylor, an outdoorsman and Maine Guide, built sporting camps on the riverbank, well away from the Moir house. In the decades he was there, he used the Moir house as a barn and hay shed.

Thomas Moir, George and Lucinda’s only son, and his wife, Elizabeth (Gardner) Moir, raised a family of 7 children on the farm with at least one marrying into neighboring farm families. Thomas’ oldest child, Annie, married a young immigrant from Canada named Daniel O’Leary. Dan and Annie settled on the far northern end of the Moir farm near a small spring-fed brook which became known as O’Leary Brook.

Dan and his wife Annie raised a family of eight children with all being born at the Moir Farm except the youngest. He was born in St. John. They lived there until illness struck Dan and they relocated their family to St. John where Dan would be closer to doctors. Before they left the farm, they managed to move and attach the small house they had built to the Moir house thus doubling the size of the farm house.

The two houses were constructed using different building styles: “piece sur piece” on the O’Leary House and timber-framed on the Moir house. As the building slowly collapses and returns to nature, the seam where the two buildings were joined together is unmistakable.

Thomas Moir sold the Moir Farm in 1906 to Frank W. Mallet and M.O. Brown of Fort Kent and Charles B. Harmon of St. John for $2,500. Henry Taylor acquired the land from them.

Henry Taylor, an outdoorsman and Maine Guide, built sporting camps on the riverbank, well away from the Moir house. In the decades he was there, he used the Moir house as a barn and hay shed. The original fields are now overgrown with spruce trees, except for where Taylor kept a strip of land cleared that was used as a runway for his plane. Henry Taylor was allowed to stay in his camps even after the State of Maine acquired the land on both sides of the Allagash River to create what was to become the “Allagash Wilderness Waterway.”

Henry and his wife Alice spent summers at the camps along with numerous guests and family, well into the 1980s.

After Henry Taylor’s death, the camps fell into a state of disrepair. A volunteer group received Bureau of Parks and Lands approval to restore one of the Taylor camps in 2004.

The volunteer group headed by Gary and Melford Pelletier started the daunting task of restoring one of the camps, taking what could be salvaged from the other deteriorated structures and incorporating them into one refurbished log cabin.

The Taylor Camp restoration project is nearing completion as I write this article. Waterway employees have assembled a small partition inside the Taylor camp made from pieces of hand hewn timbers that had been salvaged from the Moir home at an earlier date. The wall was made using the same “piece-sur-piece” construction style that was used in the O’Leary house.

After the Native Americans vanished from the area, lumber men and wilderness voyagers started traveling on the river. Many of these travelers would stop at the Moir Farm for supplies and other necessities.

In 1883, author and outdoors writer, Lucius Hubbard, did just that. Hubbard was finishing a month long journey from Moosehead Lake to New Brunswick via the Allagash River. Along with him on the trip he had an artist friend and two Native American guides. Here is a short excerpt from the book “Woods and Lakes of Maine” by Lucius Hubbard.

“Finally, as shades of night began to close about us, we reached the house of Finley McLennan, on the left bank of the stream, and all huddled about the glowing stove in that farmer’s kitchen. On our making some inquiries as to whether we might sleep in his barn over night, McLennan told us, with a knowing look, that he didn’t keep a “public house” and said we could get “something” at Moir’s a mile below, where we could put up for the night.

“There we were welcomed cordially, and were soon comfortably housed in a human habitation — the first in a month. Mr. Moir, being an old settler on the Allagash, was very well informed about that section of the country, and talked well and intelligently. He said that a good many “sporters” had passed by during the summer, and often stopped at his place for milk and eggs. When bedtime came the old couple insisted upon giving up to Sarot and the writer their bed, on which the favored guests stretched themselves and were soon fast asleep. But our slumbers did not last long, for the unusual heat from the large stove, which was replenished from time to time during the night by the good housewife, baby in arms and pipe in mouth, made us restless and wakeful.”

The good housewife mentioned in Hubbard’s book is very likely my great-great-great grandmother. How cool is that? As a ranger on the Allagash Wilderness Waterway, I am honored to have the Moir Farm in my district. I am even more honored to tell people that I am the 7th generation of O’Learys to work, live, or recreate on the Allagash River. Assistant Ranger Kale O’Leary, who also works on the waterway, is the eighth generation to do the same.

The Moir house is still standing, albeit not very straight but still standing none the less. The roof has fallen in and the walls are buckling. One can greatly appreciate the hard work it took to raise a family and gouge out a farm in this vast forest of northern Maine.